DNA-binding proteins are the center of biotech tools, from polymerases to CRISPR-Cas. Can AI help us design new ones?

Today it’s all about mixing DNA and proteins, my favourite things!

Don’t keep this newsletter a secret: Forward it to a friend today!

Was this email forwarded to you? Subscribe here!

Postdoc in the Deep North! 🥶 Okay, okay, Stockholm is not that north. But it’s cold, trust me! If that doesn’t scare you, Erik Benson is recruiting a postdoc. The position is at the edge between DNA nanotech and sequencing analysis. Erik is a cool guy (he was my master’s thesis supervisor!), and the research sounds fun! Get details and apply here.

AI Designs DNA Binders

Researchers designed DNA-binding proteins from scratch, using new machine learning tools. Image credits: Nature.

DNA-Binding Proteins: Bridging Two Worlds

DNA-protein interactions are vital to living cells.

They are crucial for gene regulation, replication, packaging, and, more recently, gene editing. Specialized DNA-binding proteins (DBPs) power these interactions.

DBPs can bind single- or double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) with two binding modes:

Non-specific: Proteins bind to DNA without a target; for example, some polymerases or histones.

Sequence-specific: Proteins recognize and bind specific DNA targets, like transcription factors.

DBPs are involved in many diseases, from cancer to neurodegenerative disease. Targeting them is really hard, and they are generally considered undruggable, even if there has been some progress.

And DNA-binding proteins are central to biotech. Basics like PCR polymerases, transcription factors for metabolic engineering, or advanced gene editing tools like CRISPR-Cas. DBPs are essential in the molecular toolbox!

These days, the spotlight is on DNA editing tools.

Zinc-finger nucleases, TALE, and CRISPR-Cas are extremely powerful, enabling incredible progress! But they also have limitations. Zinc fingers are hard to engineer, while the big TALE and CRISPR-Cas systems are hard to deliver. Plus, CRISPR-Cas systems also need a guide RNA, which adds another layer of complexity!

This limits the applicability of these systems. And you know scientists don’t like being limited!

Designing DNA-Binding Proteins from Scratch

So, can we expand the alternatives for DNA-binding proteins?

Well, the authors of today’s paper took a shot at it. They used computational design to create compact, customizable, and modular DNA-binding proteins that can recognize specific double-stranded DNA sequences!

Inspired by nature, but these new DNA binders are designed completely from scratch!

But this is not an easy problem. Designing DNA-binding proteins shares many of the same headaches as drugging them. Compared to protein-protein binders, dsDNA binders pose 3 specific challenges:

You need excellent shape complementarity so that amino acid chains can interact with the DNA bases.

DNA bases differ by only a handful of atoms, making sequence discrimination much harder than for amino acids.

Recognition relies on precise hydrogen bonds between polar side chains and DNA bases, hard to model and prone to off-target binding.

Not a challenge for beginners!

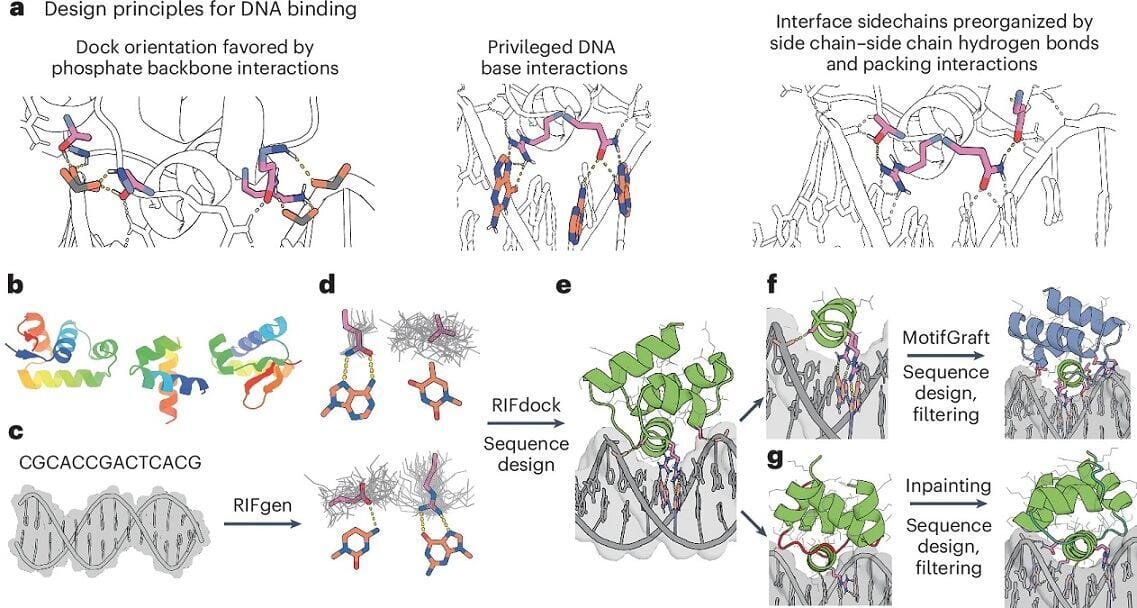

The Design Strategy

The team aimed to create small proteins (<65 amino acids), easy to deliver to cells. They focused on compact helical DNA-targeting domains, specifically the helix-turn-helix (HTH) domain.

The design pipeline has 4 steps:

Scaffold library generation

The team built a massive and diverse library of ~26,000 (!) HTH scaffolds. These were collected from sequence databases and structurally predicted using AlphaFold2, then filtered for stability. The library explores many helix orientations and loop geometries!Rotamer Interaction Field (RIF) docking with RIFdock

The researchers adapted RIFdock to DNA. RIFdock pre-computes side-chain variants that make base-specific hydrogen bonds in the major groove of the DNA. Then, it finds placements for the scaffolds that contact both DNA bases and the backbone. This constrains the geometries only to base-specific interactions, optimizing base-contact positioning.Sequence design

Promising candidates were subjected to sequence design using Rosetta or LigandMPNN (which designs protein sequences from 3D structures bound to ligands). For each DNA target, they generated 200,000 - 300,000 designs! They filtered them using Rosetta, based on metrics for binding and side-chain pre-organization.

Iterative grafting and inpainting

In the final step, the high-quality recognition domains were “grafted” into the new scaffolds, and the surrounding protein structure was rebuilt using inpainting, so that the grafted motif fits (and folds) properly.

So, a few design steps, combined with lots of filtering!

In the end, more than 10,000 designs per DNA target survived all the filtering steps.

Experiments: Do the Binders Bind?

The team took a very high-throughput approach to experimental testing.

They tested hundreds of thousands (!) of candidates across 3 design sets, comparing Rosetta- vs LigandMPNN-based pipelines.

The researchers expressed the proteins on the surface of yeast cells and exposed them to fluorescently labeled target dsDNA. If binding occurs, those cells are sorted and enriched for the next testing round.

97 designs were enriched >100x by the sorting, and 44 of them showed detectable binding! Affinities were modest (≈30–500 nM), but several binders were specific for their target dsDNA, and 5 paids were highly orthogonal to one another (they didn’t interact).

Validating and Optimizing

To check the design pipeline, the authors solved an X-ray cocrystal of one of the binders bound to its target DNA.

The DBP-48 crystal closely matched the design model, with key side-chain hydrogen bonds appearing as designed. The researchers found unexpected water-mediated and backbone-stabilized bonds, not explicitly modeled. But it helps, so all good!

They then used site maturation mutagenesis (a technique that swaps amino acids at key positions) to identify residues critical for binding. With this information, they created DBP35opt, an optimized version of DBP35.

With just 3 mutations, the affinity was boosted 500x, from ~73 nM to ~150 pM! A few, guided tweaks can turn a mid binder into a good one.

Exploring Functions: Regulating Cell Functions

But can these proteins actually work as transcriptional regulators inside cells?

To find out, the team used RFdiffusion to build protein fusions that position multiple DBP modules on DNA with precise spacing and orientation, needed to modulate transcription.

The researchers used 2 systems:

In E. coli, engineered repressors achieved dose-dependent repression of a YFP reporter driven by a synthetic promoter containing the designed binding sites.

In mammalian HEK293T cells, DBPs fused to dimerization and activation domains drove transcriptional activation, with 3-5 fold activation for several DBPs.

So, they seem to work across kingdoms!

DNA and Proteins Team Up

Great paper! Not easy to read, but cool.

And a reminder to me that DNA and proteins interact in very different ways! Sometimes, I forget (for me, everything is DNA origami). But protein-protein interactions are more hydrophobic and “patchy”, while DNA loves hydrogen bonds. So, different!

Their design pipeline worked, but it’s not without limitations.

Success rate is extremely low; it’s hard to put it into real numbers, because they tried different things, but they got just a few binders from a lot of designs and experiments. And the affinity of these binders is also not amazing!

But it’s cool that they got fully orthogonal systems! Synthetic biologists are always hungry for novel switches, and these will help. And the affinity can be improved with standard techniques!

So, go and read all the details here!

If you made it this far, thank you! What do you think of AI-designed proteins? Are you feeling some fatigue from the constant news? Reply and let me know!

P.S: Know someone interested in AI-designed proteins? Share it with them!

What did you think of today's newsletter?

More Room:

Titrating Nanoparticles: Nanoparticles are awesome and easy to work with. Most of the time. Some other time, they are a nightmare, and even basic properties are hard to get. This paper introduces a titration-inspired method to measure the molar extinction coefficients of nanoparticles, a long-standing challenge due to their complex and variable structures. By using DNA-programmable assembly, nanoparticles are forced to pair into well-defined 1:1 heterodimers with additive optical signals, allowing accurate spectral deconvolution without prior knowledge of nanoparticle composition or morphology. This robust approach enables reliable determination and cross-lab standardization of nanoparticle molar concentrations, especially when using well-defined gold nanospheres as universal titrants. Useful DNA nanotech? Count me in!

Puttin’ Metal into DNA Nanotech: Could metal be the answer to DNA nanotech struggles with biological stability? According to this paper, it might help. The study shows that inserting metal–intercalator complexes into DNA tetrahedra greatly improves their stability in serum and enhances cellular uptake, addressing a major limitation for biomedical use. Different metal complexes provide varying levels of protection, with platinum-based intercalators offering the highest stability due to stronger DNA binding and groove interactions. Overall, the work demonstrates that carefully designed metallointercalators can effectively stabilize DNA nanostructures against nuclease degradation.

DNA Origami Flex Computing: Yeah, DNA origami can make even DNA computing better. This paper presents a rigid double-layer DNA origami platform that improves the reliability of surface-confined DNA computing. By reducing structural fluctuations that cause signal leakage and crosstalk, the rigidified origami enables more accurate signal propagation with higher on–off ratios. Using this approach, the authors demonstrate low-leakage transmission lines and logic gates, providing a more robust and scalable framework for high-fidelity DNA-based computation. What can’t it do?

Share Plenty of Room with founders or builders

I help biotech and deep tech companies transform complex technologies into engaging content that builds credibility with investors, partners, and potential hires. Let’s chat!

Know someone who’d love this?

Pass it on! Sharing is the easiest way to support the newsletter and spark new ideas in your circle.Got a tip, paper, or topic you want me to cover?

I’d love to hear from you! Just reply to this email or reach out on social.