Is AI coming for genomics next?

Today, we take a look at Evo 1.5, a genomic foundational model that learns all about genomic DNA!

An awesome paper!

Don’t keep this newsletter a secret: Forward it to a friend today!

Was this email forwarded to you? Subscribe here!

AI-Born Genes

Scientists developed Evo 1.5, a genomic foundational model that learns short and long-distance relationships between different parts of the genome. Researchers used it to create novel toxin-antitoxin systems and anti-CRISPR proteins. Image credits: Nature.

Generative AI is changing the way we approach everything, from writing emails to studying biology.

In the life science world, the spotlight (and a Nobel Prize!) has gone to machine learning trained on protein sequences and structures. These models learn to predict a protein’s 3D shape, or even create new ones!

But biology is more than proteins!

At the base lies DNA, the original “language of life”. With just 4 nucleotides, it encodes the instructions that direct everything in a cell, including RNA and proteins.

Genomic DNA orchestrates the functions of each cell and transmits the information across generations. But it’s not a static recording machine: changes in genomic sequences drive evolution and enable organisms to adapt to environmental pressures.

The genome is a treasure trove of information: evolutionary history, blueprints for molecular tools, and instructions for RNA and protein production. A goldmine for research, diagnostics, and synbio!

What if a model could learn to extract this information from genomic DNA?

It would be cool, but working with genomic DNA is harder than working with proteins. Two main problems:

Data availability: Not many datasets available for your AI model!

Sequence length: Genomic DNA spans billions of nucleotides, and each one counts, with a tiny mutation changing how genes function.

Evo: Genomic Foundation Model

These difficulties didn’t stop researchers.

Just last year, a team published Evo, a genomic foundational model (a deep learning model that can be applied across a wide range of use cases, per Wikipedia). In practice, Evo predicts the next DNA base given the genomic context! I’ve actually covered it when it came out.

Evo was trained on almost 3 million prokaryotic and phage genomes, for a total of 300 billion nucleotides! During the training, the model learned short and long-distance relationships between different parts of the genome.

The result? Evo can generate DNA that looks like real genome sequences, and the predictions extend to the RNA and protein level! All by simply looking at the genome.

Amazing! But there is still room for improvement.

Evo 1.5: Training it Up

For example, it’s hard to explain to a generative AI model what the “function” of a protein should be. A little bit like defining a word without using it in a sentence.

This brings us to today’s work!

The authors (the same team that developed Evo originally) extended pretraining to create Evo 1.5. During this additional training, Evo 1.5 learned the patterns in prokaryotic genomes at multi-kilobase scale, like gene neighbourhoods, codons, and operon patterns.

But why did they do it?

Well, the core idea is to create a new paradigm for functional protein design. This new approach doesn’t tell the model “make a protein that does X” and doesn’t fine-tune it on a single task.

They went a different route: semantic design.

Semantic Design: Guilty-by-Association Genes

The team hypothesized that, similar to how you can understand a word’s meaning from the words around it, you can learn a gene’s function from the genes around it.

They named this new strategy semantic design.

They feed Evo 1.5 a prompt consisting of a real genomic context, and then ask it to complete the DNA sequence.

Their idea is that if the model learns when genes are present together, it will generate sequences that are functionally related to the provided genomic neighborhood.

So, the generated sequence will be enriched for the function implied by the prompt.

This strategy works great on prokaryotic genomes, where functionally related genes are often grouped, like in operons or anti-phage defence islands.

By simply providing the genomic “context”, Evo can generate functional sequences. No need for structural models, expensive retraining, or a priori mechanistic hypotheses!

From Sequence to Bench: Selection & Filtering

So, you prompt Evo with a genomic context, and it generates a huge number of functional sequences.

Now, it’s impractical to test them all. So, the authors used multiple in silico filters before ordering DNA for experimental validation. Some examples:

Oper reading frame detection, codon checks, and length filters to ensure the DNA sequence makes sense

Structural and functional screenings: structure predictions, predictors for functional likelihood, and annotation tools

This way, the authors generated a manageable set of candidates!

To The Bench!

Okay, now we know how it works. What did the researchers build?

The team focused on 2 multi-component, context-dependent systems: toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems and anti-CRISPR (Acr) proteins. Both are often encoded in operons, and their function is heavily dependent on the genomic context.

Let’s dive deeper!

1. Type II and type III toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems

Phages and bacteria have been locked in an arms race since forever.

Phages harm the bacteria, the bacteria respond, and so on. This created fast-evolving defence systems, with lots of functional diversity and limited sequence conservation.

The perfect stress test for Evo 1.5!

TA systems maintain a delicate balance between producing a toxin and a neutralizing antitoxin. If a phage infection destabilizes this balance, the bacteria essentially kill themselves, slowing the phage’s spread. Brutal! These systems are classified based on the antitoxin: type II → protein, type III → RNA.

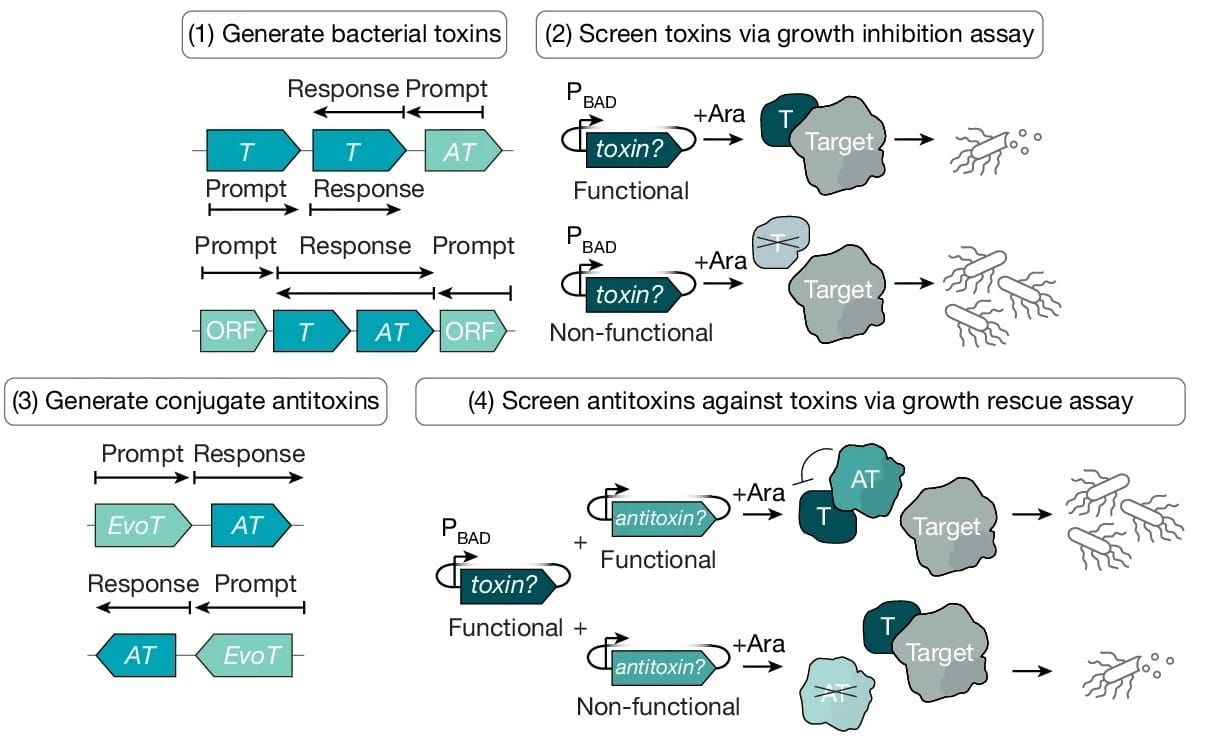

The workflow here looks like this:

Prompt with genomic neighborhoods

Generate toxin candidates

Screen for toxicity

For functional toxins, repeat the process to create antitoxin candidates

Screen for rescue of bacterial growth

And there you have, a perfectly functional toxin-antitoxin pair!

The authors achieved high experimental success rates for the functional TA pairs, ranging from 17 to 50%. And they only tested tens of variants!

One example: EvoT1, a generated toxin, arrested growth when induced. The generated antitoxin EvoAT6 completely restored it!

Crucially, the TA pairs showed no sequence similarity to existing systems, confirming that Evo is testing new sequence spaces.

2. Anti-CRISPR (Acr) proteins

On the other side of the war, phages evolved anti-CRISPR (Acr) proteins to defeat the bacterial CRISPR defence system.

The team kept the same workflow here (pretty cool ah?):

Prompt Evo with the genomic context (Acr loci)

Generate candidate proteins

Filter the candidates in silico for structural soundness and functional capabilities

Test for the ability to inhibit Cas9-mediated activity

Evo produced functional anti-CRISPR proteins, including some with no clear sequence or predicted structural similarity to known Acr families.

SynGenome: Over 120 Billion Generated Bases

As the cherry on top, the authors used Evo 1.5 over millions of natural genomic prompts and created SynGenome, a public database of more than 120 billion generated base pairs!

The team aims to help other researchers explore the huge variability of synthetic and natural prokaryotic genomes! It will be interesting to see if we can discover novel protein functions in there.

Takeaways: Is the Future Semantic?

Super cool work!

This new semantic design produced functional de novo genes with high hit rates. The resulting products often look nothing like their known counterparts! Truly novel.

Crucially, this approach doesn’t require prior structural knowledge or task-specific fine-tuning. It could be complementary to other methods for exploring new paradigms in protein design!

Of course, they trained and developed Evo only for prokaryotes. Genomic organization is very different in eukaryotes, so it will probably not work there.

Finally, biosafety is a critical factor. When dealing with synthetic biology, it’s essential to be proactive against misuse by bad actors. Especially for SynGenome, I would have liked a discussion about biosafety!

But go here to read the paper and learn all the details that went over my head! What’s your favourite idea in there? Reply and let me know!

P.S: Know someone interested in AI and genomics? Share this with them!

More Room:

Light-Assembled Organelles: Assembly and disassembly are basics in living systems, but we scientists have a hard time recreating the fine control nature has. This study developed a light-controlled system in which synthetic azobenzene-based molecules assemble and disassemble on organelle membranes. These molecules form membrane-binding fibrils in their trans form, but UV light switches them to a cis form that breaks the fibrils into weaker, amorphous structures. Visible light reverses the process. Repeated light-driven switching cyclically strengthens and weakens membrane interactions, ultimately disrupting organelle membrane integrity.

Activating Green Nanomaterials: It’s time for nanomaterials to take center stage on the sustainability stage, according to this study. The authors describe a shift from traditional, passive “green” nanomaterials toward programmable nanomaterials that can actively sense and respond to their biological environment. By combining tools from synthetic biology, DNA nanotechnology, AI-driven design, microbial engineering, and 4D bioprinting, researchers are creating nanomaterials that can process biological signals and adjust their therapeutic actions in real time. These advances could lead to autonomous, self-regulating nanomedicines that behave more like living systems, though challenges in stability and large-scale manufacturing remain. Interesting!

Metal Transitioning To Microscopy: If you think that cells are not the place for transition metals, think again. This article reviews how metal complexes, with their customizable optical and luminescent properties and strong resistance to photobleaching, are emerging as powerful imaging probes for optical super-resolution microscopy. By choosing complexes with suitable photo-excited behaviors, researchers can use them across various super-resolution techniques to visualize cellular structures and dynamics at the nanoscale. The review also discusses current limitations of molecular probes and outlines future directions for developing better tools to further expand the capabilities of super-resolution imaging.

What did you think of today's newsletter?

Share Plenty of Room with founders or builders

I help biotech and deep tech companies transform complex technologies into engaging content that builds credibility with investors, partners, and potential hires. Let’s chat!

Know someone who’d love this?

Pass it on! Sharing is the easiest way to support the newsletter and spark new ideas in your circle.Got a tip, paper, or topic you want me to cover?

I’d love to hear from you! Just reply to this email or reach out on social.